About the Guest Blogger

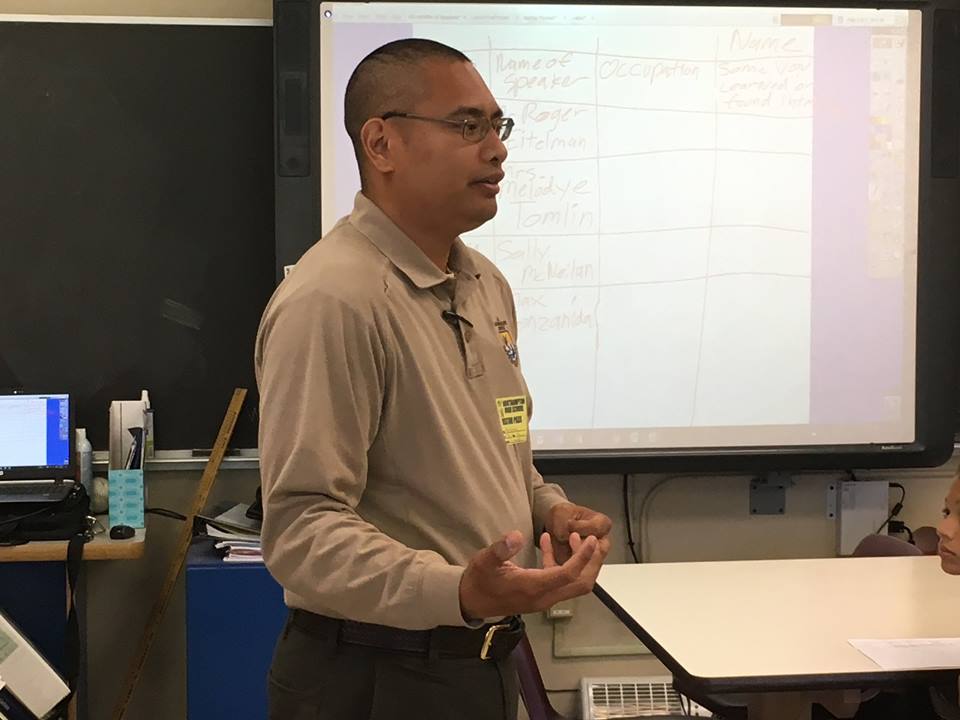

Max Lonzanida, visitor services park ranger, Eastern Shore of Virginia National Wildlife Refuge.

Max manages everything that has to do with wildlife-dependent recreation on the refuge. He commutes to the Shore daily from Norfolk, where he lives with his wife Amy, his two energetic kids Noah and Stella and their two dogs.

The Secret Fisherman’s Island

Get a rare glimpse of Fisherman’s Island, which is typically closed to the public except during winter weekends. It’s part of a 2,000-acre refuge on the very tip of Virginia’s Eastern Shore.

If you’ve traveled over the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel to and from Virginia’s Eastern Shore, you’ve visited Fisherman Island. Route 13 takes you across the island in the blink of an eye and you’re either in Northampton County or over open water on the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel. What a lot of people don’t notice is the gate and small parking lot just along the bend in the road; and more importantly, what lies beyond that gate.

If you happen to get up early enough on a Saturday morning from October to March, you’ll get a chance to see what lies beyond the locked gate, unprecedented wildlife viewing. You can spot Buffleheads, Surf Scouters, Great Blue Herons, American Bald Eagles, and even White-Tailed Deer; and that’s just the larger creatures that call this island home.

Since the island is a National Wildlife Refuge, it’s only accessible after nesting season is over. During any given tour season, less than 600 people set foot on the island during guided eco-tours offered by park rangers from the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service and dedicated volunteers from the Eastern Shore Master Naturalists.

How do you get on the island? It’s free. Our refuge runs tours at either 7 a.m. or 9 a.m. on Saturdays from October through March. You can sign up by emailing me at max_lonzanida@fws.gov or leaving me a voicemail with that information at (757) 331-2760 ext. 114. Either way, once you’re booked in, you’ll be one of less than 600 people each year to experience everything that the island has to offer.

The History of Fisherman’s Island

Jack Humphreys and Joe Beatty, both dedicated tour guides from the Eastern Shore Master Naturalists, will tell you that the island formed after a linen ship sank in the inlet in the late 1900s. Locals scavenged the linens and left the ship in place. Over the years, sand started to accumulate around the wreck and an island was formed.

That’s just one of the theories of how the island was formed, you’ll have to go on the tour to learn about the others.

The federal government purchased the island in 1886 from a William Parker. The government used the island as a quarantine station; complete with a barracks that could house up to 1,000 individuals, a kitchen and keepers quarters. The island was home to 13 employees. Records show that in 1893 the island was used to quarantine the ship Despa, which was suspected to carrying passengers who were ill with yellow fever.

With the advent of WWI came the use of the island as a coast defense artillery fortification. In 1943 the island, in conjunction with Fort John Custis (the predecessor to our main refuge) was home to up to 200 soldiers who manned observation towers and generators, operated 300 mines and stood watch at the 90mm and 6-inch gun batteries that were found on the island.

The island was clear cut of vegetation, and pictures from that era reflect that. The island was used after the war as a radar site and was finally turned over to the U.S. Department of Interior as a National Wildlife Refuge in 1973. In 1984, it was absorbed into the larger Eastern Shore of Virginia National Wildlife Refuge.

So what happened to the island after the military left? Well, we let nature take its course. The bunkers and fortifications, toppled towers and mangled pieces of Marston mats used as hasty roadways are still on the island, along with the paved road that was used. They’ve either been overgrown with brush or, as is the case with the roadway, turned into walking trails.

The primary purpose of the refuge is to serve as breeding grounds and nursery for marsh and water birds, shorebirds, gulls, terns and allied species. Its salt marsh serves as an important wintering habitat for black ducks and brants. The beach and sandbars host cormorants, loons, gannets and gulls who feed over the water. Along the beach are scores of ghost crabs which scurry from their holes as visitors walk by. When the timing is right, the island is home to thousands of snow geese migrating through; which is a spectacle to see and hear during the tours.

The island is identified as an important birding area by the National Audubon Society, recognized by the RAMSAR convention of 1971 along with the rest of Virginia’s barrier islands as a wetland of international importance, and a birding hotspot.

About the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

The Mission of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is to work with others to conserve, protect and enhance fish, wildlife and plants and their habitats for the continuing benefit of the American people.

Comments are closed.